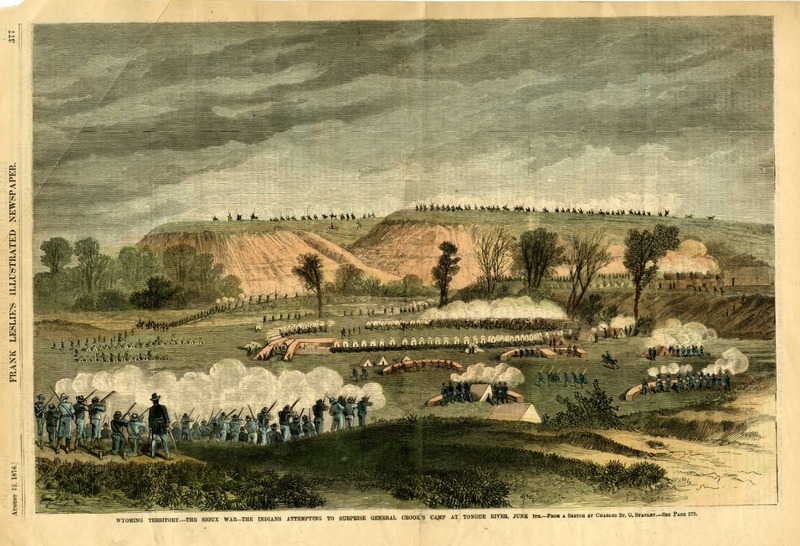

On this #TBT, we remember the often overlooked skirmish at Tongue River Heights.

On Friday, June 9, 1876, Brig. Gen. George Crook’s Big Horn and Yellowstone Expedition had been camped in a stand of cottonwood trees at the confluence of Tongue River and Prairie Dog Creek for two days. Waiting for the return of three scouts (sent to enlist Crow warriors for a campaign against off-reservation Sioux and Cheyenne), the approximately 950 soldiers and 100 civilians passed the hours in various ways. Soldiers raced horseback and “packers” raced on foot across the adjacent open flat.

That night, as everyone was finishing dinner, shots were fired by men tending the picket line to the east. What happened next was described by 3rd Cavalry Lt. James E. H. Foster in a dispatch to the Chicago Tribune. “We had not time to even express and form an opinion as to what was the matter with the picket, when a rattling volley was fired into the camp from the heights on the other side of Tongue River, and a number of Indians were seen running about the crest of the cliff, firing their breechloaders and making themselves especially unpleasant and remarkably noisy, while one who appeared to be principal musician in the serenade kept galloping up and down as though he had lost something and was in a great hurry to find it.”

“If the afternoon races didn’t put an end to the boredom of camp life,” author Marc H. Abrams wrote, “the bullets recklessly being fired in and around the soldiers’ tents and wagons certainly did. The skirmish at Tongue River Heights, one of the least written events in the Great Sioux War, was underway.”

Joe Wasson, writing for the New York Tribune and Daily Alta California, also described the opening moments of the skirmish. “The bullets ‘zipped’ in among our tents, horses, and wagons, in a way extremely interesting,” he noted. “The soldiers, teamsters, etc., returned the fire at once.”

Wasson described the seemingly reckless behavior of the Indians as they rode “up to the edge of the bluff in very plain sight for an instant, only to turn and fall back out of range.”

Civilian Charles St. George Stanley described one particularly memorable warrior. “He was mounted upon a white war pony, smeared with great bands of vermillion, and his head adorned with a coffee pot, brightly burnished and decorated with eagle plumes. This individual rejoiced in the sobriquet of ‘The man with the Tin Hat,’ and it was his business to pass rapidly backwards and forwards upon the side of the ridge, in order to draw the fire of the troops, thus enabling his comrades to fire into us with impunity. His appearance was so striking that he naturally attracted the attention as well as the fire of the command, although without effect, as the confounded rascal seemed to bear a charmed existence. At this juncture some of the packers displayed an utter disregard for personal safety, and running to the river bank…turned handsprings and somersaults, yelling at the top of their voices, ‘head him off!’ ‘hobble him!’ ‘nosebag him!’ and other kindred expressions peculiar to their profession, until the thing became really amusing.”

Crook and other senior leadership were not as amused. The Indians’ ability to keep the soldiers pinned down indefinitely, plus the soldiers seeming inability to even wound a single Indian, was an embarrassment, not to mention a waste of ammunition. Four cavalry companies were ordered to cross the river, ascend a steep, rocky ravine, and “clear the heights” of Indians.

John F. Finerty of the Chicago Times accompanied the cavalry across the river. “Then we commenced to climb the rocks, under a scattering fire from our friends, the Sioux. The bluffs were steep and slippery, and took quite a time to surmount.”

Once the soldiers reached the summit of the bluff, the Indians proceeded to lead them on a frustrating chase. The warriors would scamper up the next rise, stop, turn, and fire, only to repeat the process each time the cavalry advanced.

“[Some of the soldiers] had their feelings hurt because the Indians could not be induced to give the battalion who went after them a respectable fight,” Foster stated. “If they had done what everybody had expected, they could have inflicted serious loss on us as the line ascended the hill….”

The soldiers returned to camp. And thus, after about one hour, ended The Skirmish at Tongue River Heights.

With a few injured horses the extent of their casualties, the Army was able to take a generally lighthearted view of the incident. Crook was chastened however and posted a company of cavalry on the bluff for the remainder of their stay.

It turned out that the attackers had been a horse-stealing expedition of about 100 Northern Cheyenne. Their village was located at the junction of Muddy Creek with the Rosebud, about 45 miles north of Crook’s camp.

Eight days later, Crook’s army, including more than 250 Indian scouts, would fight the Sioux and Cheyenne in the largest Indian-soldier conflict in the history of the Plains Indian Wars, the battle of the Rosebud.

Another eight days later, Sunday, June 25, those same Indians made history for their celebrated victory over George Custer and the 7th Cavalry at the Battle of the Little Big Horn.